By Dr Peter Standring, technical secretary, Industrial Metalforming Technologies (IMfT)

Without any doubt, the two factors in my own lifetime that have created the world in which we live are globalisation and standardisation. Globalisation in all its varied forms affects every aspect of life – including the planet itself. Standardisation is a factor because it is utterly impossible for us to do what it has taken the natural world one billion years of evolutionary trial and error to achieve; namely to produce 7.5 billion living customised humans.

Historical trends

Until the start of the ‘digital age’ (electronics only made this possible) the progress of manufacture moved in lock-step with the weapons of war. From the beginnings of history, those having the resources, organisational skills and the desire to create more and better weapons of war, invariably won the argument. Whether land or sea-based Empires, all developed the means to mass produce the equipment to fight with.

The most efficient created assembly lines whereby ships, swords, etc, could be produced to an agreed standard form. With the introduction of firearms, the demanded accuracy, larger numbers, maintenance, and repair, brought about the parallel development of the machine tool and metal production industries. Such spin-offs were rolled out to the general population creating facilities able to supply both commercial and domestic markets with the same manufacturing capabilities. This in turn led directly to an explosion of entrepreneurial activity with individual local manufacturers producing their own versions of similar products.

The gravitational effects of the aggregation of local manufacture produced the distribution of 19th and 20th century industrial centres, which often remain today.

The natural consequence of all these embryonic developments gave rise to a multiplicity of independent manufactured options to serve the same purpose. Roll out the respective government demands for weapons of war and this introduced an absolute requirement to:

- Standardise on what was produced.

- What it was produced from.

- How it was produced.

This thrust for rationalisation was refined in both World Wars. The post war period saw a wider adoption of the means of manufacture developed by wartime emergency. In particular for this article, the ability to successfully cold forge steel developed in Germany in the late 1930s and kept as a state secret throughout the war. In 1960 – 1969, this became a collectively funded programme shared by OECD countries as a novel high-tech operation to be exploited by national and multinational enterprises.

Big business soon discovered it was easier to acquire market share through acquisition and merger than by growing the market, which in turn led directly to the rationalisation of back office operations and products.

Deproliferation was the term coined by General Motors for a programme designed to standardise and rationalise the billions of components it used. In 1994, this author attended a presentation by the Opel Manager of Fastener Development and Coordination concerned with the reduction of welded studs used by the company in Europe. On their CAD system they had over 800 different components many being obsolete or varying in size by only a few millimetres. The cost of keeping each part on the CAD system was 12,000 DEM per year (in 1994 1 DEM was worth US$0.57). Using only what they needed, the number of active parts was reduced from over 800 components to just 17. This saved GM around DEM 40 million a year and resulted in the design control shifting from engineers to the deproliferation unit.

Presenting another excellent example of ‘rational’ thinking, the deproliferation unit determined that on engines, there were 22 different fasteners used in six different working environments. These required six different coatings/treatments. Using ‘focused’ research, the unit were able to identify a single surface treatment that could cost effectively satisfy all the environmental demands.

As a final point, the GM presenter ended with a comment that his team had surveyed the whole European automotive industry and concluded that if all OEMs and tier ones standardised their fastener product range, the total annual output could be met by just six large manufacturing units.

Much has changed in the intervening 27 years with the explosion of manufacturing developments in central/eastern Europe and the Far East. However none of these have changed the inexorable trends of globalisation and standardisation. Despite the economic shake ups of 1998/9 and 2008/9 and the current supply chain wobbles resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, reshoring is, as yet, only a dream to be wished for by those who are in desperate need.

Manufacturing trends

Henry Ford’s grand vision of a company that could make everything in-house (vertical integration) was quickly proved to be infeasible. Specialist producers of special products, e.g tyres, glassware, non-standard metals, etc, were clearly focused on doing what they did best and what they produced was both better and cheaper than what the Ford Motor Company could provide. So, Ford had two choices; buy them and take the products they made off the open market or contract them to supply Ford (horizontal integration). And so, the supply chain concept was established.

Clearly, in a mass market, the greater the mass, the bigger the profit (assuming the business case is sound). Investing those profits to grow the business means new opportunities, increased facilities, higher output and even better returns. It was this rush for growth in the late 19th, early 20th centuries – in the USA particularly – which led to the term, Industrial Robber Barons. Perhaps not inappropriate for those involved in today’s Big Tech companies...

What is absolutely clear is the fact that, to be ‘big’ requires the facilities to produce ‘big.’ The question then arises, who determines the market?

Pick up any article that links customers to products and the term ‘supply and demand’ is likely to be found, always presented in that order. So, does this mean ‘supply’ comes before ‘demand’ or, as many would suggest, the ‘demand’ must be there in order to ‘supply’.

Assume you are a very large supplier with hectares of manufacturing space and run a highly efficient organisation. Then, for whatever reason, a global pandemic; a nuclear winter following an eruption of a super volcano; a devastating solar blast of radiation, which knocks out virtually all global communications; how long could you survive if there is no demand?

Likewise, as in the case of recent panic buying of fuel, energy, some food and even toilet rolls. If the ‘supply’ is no longer available what can be done to meet the ‘demand’?

The logistics, which facilitate the smooth running of all mass production, incorporating ordering, delivery, in-house manufacture, despatch, documentation and tracking, makes the Just In Time (JIT) concept a reality. And yet, similar to the Chaos Theory where the fluttering of a butterfly wing in one part of the world can create a storm in another, recently when a container ship blocked the Suez Canal many waves were created in the JIT supply chains.

In a globalised and highly standardised world, when things work well the customer will benefit from a slick and unseen operation. Throw any large spanner in the works and the inevitable will happen.

Possible perturbations

In 1989 the tectonic plates of global politics changed. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the command economies of many communist states imploded. After a madcap free for all, these have adopted a general ‘Capitalist’ approach. Like all of manufacturing, the enabling factor has been ‘digitisation’. In China that year, the student protest in Tiananmen Square was dealt with in a different manner. In 1993, the Chinese Premier made the first visit to the USA. Before reaching the White House he gave a speech at a dinner in his honour by the rich and famous of L.A. In this, he stated that after much research and reflection, the Chinese Communist Party had concluded that the economic arguments proposed by Karl Marx were incorrect. So, the Chinese State was now adopting the capitalist economic model and would use it to defeat the capitalist system. The rest, as they say, is history.

The simplistic tools China has used in achieving its manufacturing dominance have been the price and profit of those overseas players they dealt with. Or put more brutally, fear and greed. Buy cheaply from us and make large profits back home and by doing so, you can help destroy the manufacturing capabilities where you are based.

A contact who worked for a multinational automotive manufacturer, which set-up a 50-50 joint venture in China, stated after his first visit: “We spent 100 years developing this technology and have just given it all away.” The carrot; to have access to the rapidly expanding Chinese market, the cost, to provide an on-the-job, 24/7 training programme using only cutting edge international manufacturing methods.

When China joined the World Trade Organisation at the turn of the century, most other nations supported this in anticipation of a gentle merging of shared interests leading to mutual benefit. What none of them realised was they had caught a tiger by the tail. Interestingly, recent government actions in China suggest that the period of free reign, free market expansion has passed its high water mark and the economic model is beginning to change? Watch this space.

Global business works well when it operates on a flat and level playing field. Given the current political tensions, this doesn’t provide comfort to those in the global supply chain.

Standard versus non-standard

Competition is the essential driving force of a capitalist system. Monopoly is the minimum energy consequence of a ‘command economy’. Strangely, as in the case of the previously mentioned Industrial Robber Barons of yesteryear, the reason for their overthrow was because of the monopolies they created in the capitalist market.

As in the natural world, big fish tend to get bigger by removing the competition from their area of operation. To ensure they don’t get too big to handle, governments introduce forms of regulation, which are designed to create a rules based environment. However, swimming alongside these international leviathans are the minnows that feed on the swirling currents the big beasts leave in their wake. So, if the trends presented above continue, the stark choice faced by virtually all manufacturers of fasteners is whether to link their business to main stream supply chains or to seek an existence outside.

As always, the first consideration is finance. Being a small player doesn’t involve too much, being large requires plenty.

The term, standard fastener, refers to the multitude of commonly used fasteners which over time have had their specifications ‘standardised’ by independent national bodies. Special fasteners is a term normally used for those components that have ‘above standard’ specifications, generally related to their ‘critical’ safety or special purpose attributes. These are often known by a trade name.

Standard fasteners are high volume use, specials generally less so. The key here is the ‘demand’. General purpose fasteners used globally are required in very large numbers, specials less so. The volume determines the value and therefore, non-standard fasteners can have a value many times greater than an equivalent standard part. Imagine the value of a ‘special’, flown halfway around the world to solve a high cost emergency compared with a similar ‘standard’ available from any engineering stores.

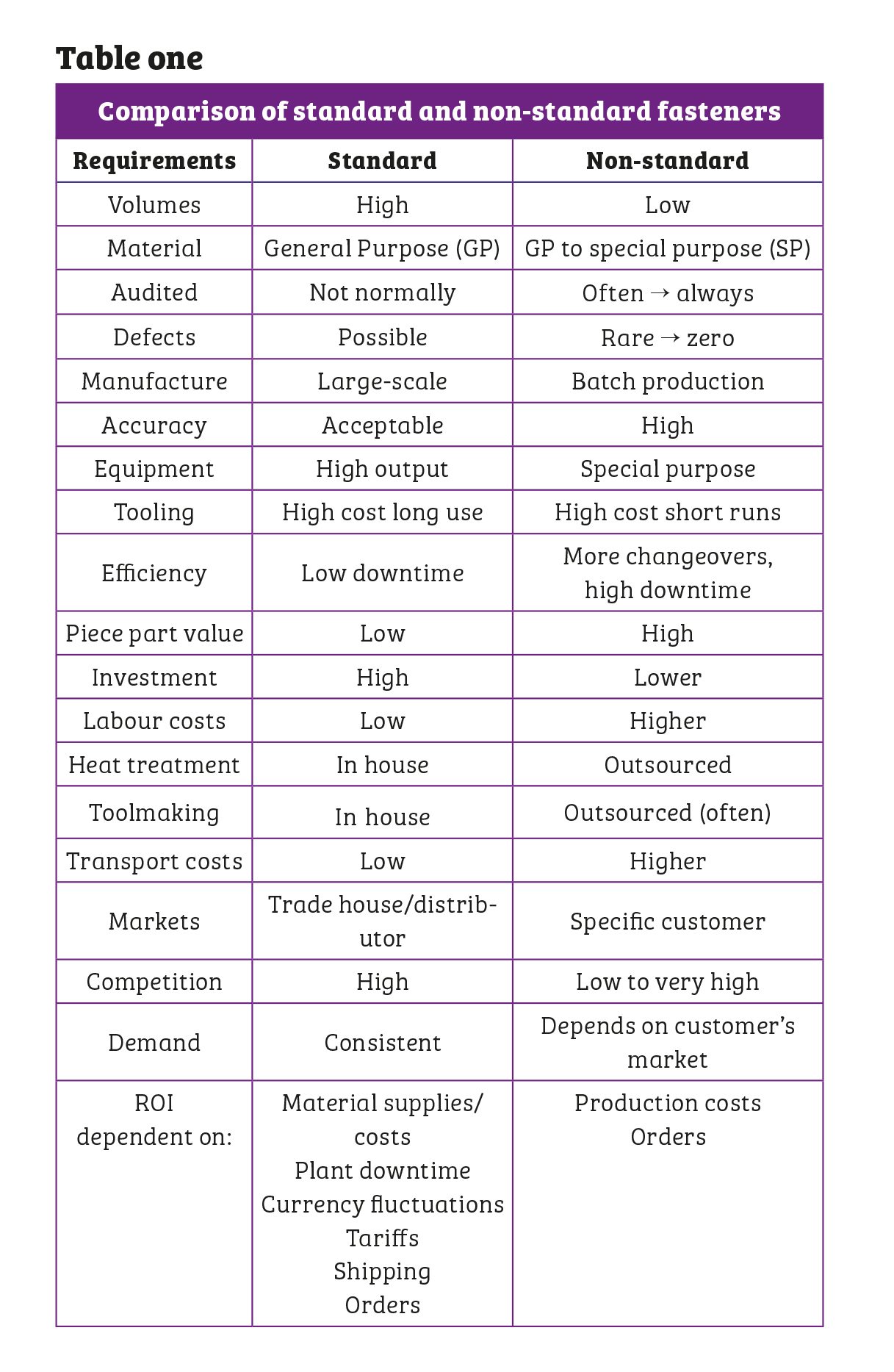

For these reasons, the manufacturers of fasteners face very complex circumstances irrespective of which of these products they produce. These are outlined in ‘Table one’ (right).

Evaluation

Few investors would risk having their entire shareholding in one stock. For them, diversification is the key to sleeping well. With most manufacturers, the choice is not so simple.

As ‘Table one’ shows, the producer of standard fasteners must operate in a market where mass production is the only option. Sure, people can operate very profitably producing standard fasteners that are now obsolete and therefore no longer classed as ‘standard’. In today’s market, these are classed as ‘specials’ and have a higher value. Since standard fasteners are required to be produced in very large numbers, the investment in materials, equipment, tooling, etc, must also be very high. By the same token, any fall off in demand, unanticipated fall-off in output, currency fluctuations, changes in trade tariffs, etc, will hit hard. As with most things, when times are good and conditions stable, those who operate in the mass market can make serious profits.

Contrast that with the smaller producer of non-standard fasteners. They often have a more diverse customer base, a wider portfolio of products and must accept the downtime of equipment due to the need for batch production. This naturally involves greater manual interaction, an increased range of labour skill sets and an ability to have flexible working at all levels. For the non-standard fastener manufacturer, the sleepless nights could arise from the fragility of the customer’s market; the poaching of both business and staff by equivalent competitor companies; and the need to continuously extend the range of the company’s technical capabilities to stay ahead of the game.

Where to from here?

Will globalisation continue? Modern communications provide 24/7 coverage, which show those who are able to receive them, just how everyone else lives their lives. This in turn creates demand, whether from those migrating to where what they want can be had, or by those who choose to stay at home. Only governments, acting on behalf of their own people, can throw a big spanner into this, or to use it to make things work better.

Also, if globalisation continues at the increasing pace it has been doing, then standardisation of the market choices will inevitably follow.

Fasteners for flatpack furniture, ring pull drink and food cans are standardised because it makes commercial sense to do so. Unique market identity of a smart phone, electric vehicle, an iconic building or a high-speed train is only a design feature that covers a series of parts, which together make it function. And, as always, at the core of these are the fasteners that hold the whole thing together. Standard or non-standard, without them, nothing would work.

Biog

Will joined Fastener + Fixing Magazine in 2007 and over the last 15 years has experienced every facet of the fastener sector - interviewing key figures within the industry and visiting leading companies and exhibitions around the globe.

Will manages the content strategy across all platforms and is the guardian for the high editorial standards that the Magazine is renowned.